Copying in Music Production: Why It Works – and Where It Stops.

- Leiam Sullivan

- 1 day ago

- 3 min read

Let’s be honest: familiarity gets rewarded in music.

It always has.

Genres are built on shared language. Scenes move because ideas repeat. Tracks that feel recognisable travel faster than ones that challenge the listener too early. Algorithms, playlists, even audiences themselves tend to favour what already sounds like it belongs.

None of this is new.

None of it is surprising.

In fact, for a long time, imitation can feel like progress.

Here's the reality

I know a producer who copied a big track part for part – and ended up with an even bigger track of their own.

When I say part for part, I mean element for element. When the hats came in, their hats came in. When the lead dropped, theirs dropped – a different lead – but at the same moment. The sounds were changed, but the structure didn’t.

Back in the early days of production, arranging was an actual job – a specialist one. And it really is an art. It’s about controlling energy and emotion in the best possible way: when to excite, when to hold back, how to give the listener the right experience at the right time. There’s a real skill to that.

By copying, all of that work was already covered.

It worked because the blueprint was already proven – and because they executed it cleanly.

Why copying works (and why we all do it)

Most of what I know was built through copying.

That’s how we learn.

You copy until the shapes make sense. You copy until the language becomes familiar. You copy until you can hear why something works, not just that it does.

Up to that point, everything can be worked on – and everything can be supported.

If you don’t know music theory, you use tools as you learn.

If you want real instruments, you bring in session players.

If you want the best possible mix, you get it mixed.

None of this disqualifies the music.

It sounds obvious, but in today’s world there’s an expectation that producers should do everything themselves – write, arrange, sound design, mix, master, brand, deliver. That’s not how great music has historically been made.

The goal isn’t self-sufficiency.

It’s expression.

The place beyond copying

There’s a point – and it only comes after you’ve put the work in – where you stop thinking about all of that.

You’re not referencing.

You’re not checking boxes.

You’re not asking what should happen next.

You’re just writing.

In the energy of the delivery, you're splashing paint on the canvas. Being the deliverer rather than the planner.

For me, that’s the place.

It’s not careless. It’s not naive. It only works because you already know what needs to be done. The craft is there – it’s just no longer in the way.

The quiet limit of imitation

This is where copying reaches its limit.

You can build perfectly functional tracks by borrowing structures, energy maps, and proven decisions. You can get very far that way.

But that state – the one where you’re simply delivering – can’t be copied.

You can’t fake timing when it’s felt.

You can’t fake restraint when it’s honest.

You can’t fake expression when there’s nothing to hide behind.

That’s not about skill anymore.

It’s about truth.

Truth isn’t purity – it’s freedom

Working in truth doesn’t mean rejecting influence or pretending you exist in isolation.

It means you’re no longer hiding behind influence.

You stop borrowing certainty from other people’s decisions.

You stop needing familiar structures to justify your choices.

You stop masking uncertainty with things that have already been approved.

Ironically, this is when ideas come more easily.

Because you’re no longer filtering every move through comparison.

You’re listening again.

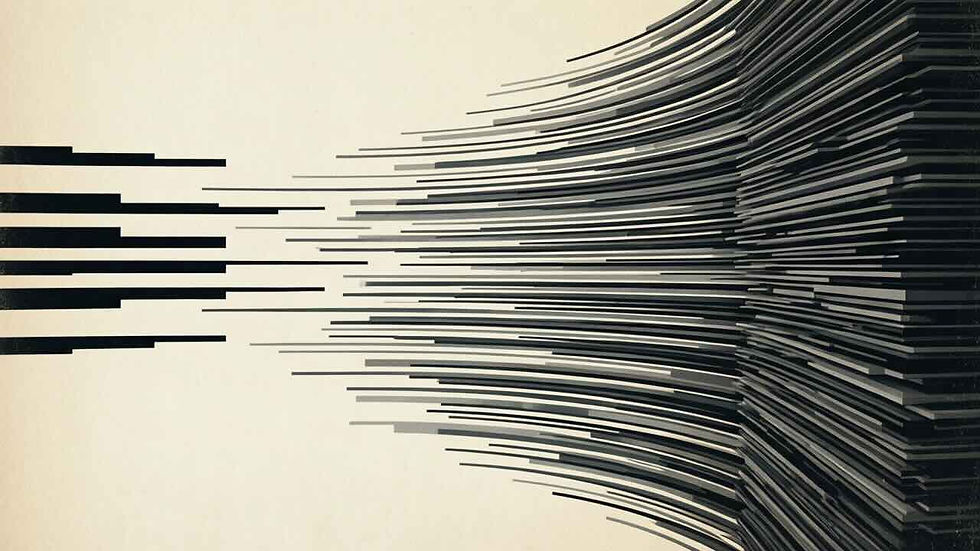

The signal problem

Music is full of signals.

Some ideas are repeated so often they blur into background noise. Others fade because they never quite find a voice. A few carry something personal enough that they cut through without forcing their way in.

Eventually, everyone has to decide whether they’re repeating a signal – or transmitting one.

That choice doesn’t announce itself.

It arrives quietly.

You feel it in how you work – and whether the work still surprises you.

Where copying belongs

Copying has its place.

It’s a tool.

A phase.

A way of learning the language.

But it’s not where connection lives.

Connection happens when the work could only come from you – not because it’s unprecedented, but because it’s aligned.

Listeners feel that alignment, even if they can’t explain it.

And once you’ve worked there, imitation starts to feel strangely loud.

Not wrong.

Just empty.

Comments