The Bell EQ Trick: A More Musical Alternative to High- and Low-Pass Filters

- Leiam Sullivan

- Dec 20, 2025

- 3 min read

High- and low-pass filters are everywhere in modern mixing. They’re quick, they’re tidy, and they’re often the first thing we reach for.

But they’re not always the most musical choice.

One technique I’ve come back to over the years – and one associated with engineers like Mick Guzauski – is using wide bell EQs on the top and bottom instead of filters.

Not as a rule. As an option.

Where this idea comes from

In interviews and long-form mix breakdowns, Mick consistently talks about preserving the integrity of a sound rather than cleaning by default. He’s cautious with anything that removes information too decisively, and that includes aggressive high- and low-pass filtering on musical sources.

If you look at his sessions, you don’t see filters stacked everywhere. Low end is controlled by balance and tone. Top end is shaped without that tilted, hyped feel. Broad, gentle EQ moves come up again and again.

Steep filters create abrupt phase shifts at the cutoff, which can subtly flatten a soundstage.

He’s also spoken about being sensitive to phase changes and how subtle EQ decisions affect the feel of a mix, not just the frequency response. Filters – especially when used across lots of channels – can quietly change that feel. Wide bell curves tend to do less of that.

That mindset made me start reaching for wide bells in spots where I’d usually grab a filter.

Why high- and low-pass filters can be heavy-handed

Filters are decisive. Once you set them, everything beyond that point is gone.

That’s fine for:

Cleaning noise

Removing rumble

Tightening badly recorded material

But on musical sources, they can:

Thin things out too quickly

Shift the balance in a way that feels “processed”

Affect phase and tone more than you realise

Especially when they’re stacked across lots of channels.

The bell EQ alternative

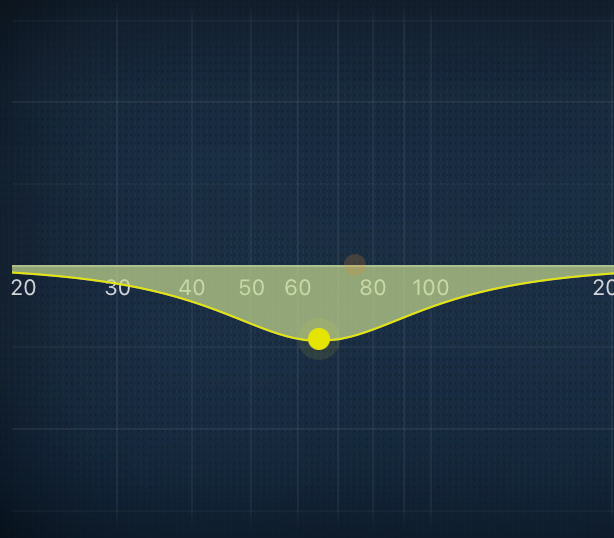

Instead of cutting everything below or above a point, try this:

Use a wide bell

Make a small cut

Target the area causing the issue, not the entire range

You’re shaping tone, not enforcing a boundary.

Practical examples

Low end: bell instead of high-pass

Rather than a steep high-pass at 80 Hz:

Try a wide bell cut around 60–120 Hz

Keep it subtle

Let the true low end breathe

This keeps weight and movement while reducing muddiness.

High end: bell instead of low-pass

Instead of low-passing the top:

Use a wide bell around 8–14 kHz

Gently tame harshness or excess brightness

Preserve air without dulling the sound

This is especially useful on vocals, synths, and buses.

Why this often sounds more “musical”

Wide bells:

Have a centre of gravity

Rise and fall naturally

Interact more gently with compressors

Wide bell curves also tend to introduce gentler phase shifts than steep filters. In practice, that often means depth, punch, and stereo image feel more natural – especially once compression and summing come into play.

Filters don’t taper – they remove.

That difference adds up over a whole mix.

When filters are still the right tool

This isn’t anti-filter.

Use high- and low-pass filters when:

There’s clear noise or rumble

You need strict separation

You’re solving a technical problem

Use bells when:

The problem is tonal

The part already sounds good

You want control without sterilising the sound

Closing thought

Mixing isn’t about rules – it’s about intent.

Sometimes the goal isn’t to remove frequencies, but to nudge the balance into place. Wide bell EQs give you that option, and once you hear it, it’s hard to unhear.

Next time you reach for a filter, try a bell first. You might keep more of the music than you expect.

Comments